About Eddie Kamae

For Edward Leilani Kamae music was the language of life. He said a song wasn’t finished until it brought tears to his eyes. He searched for forgotten songs and reinterpreted them in a style that was both traditional and new at the same time. He used music, and later, film, as a means of cultural preservation, seeking out and sharing the songs and stories of kūpuna as his teachers encouraged him to do. They told him to do it for the children, for the generations yet to come.

His talents and achievements are legendary. The New York Times called him one of the most important musicians of the second half of the 20th century. A career that spanned five decades was marked by innovation and preservation, and his passing in 2017 left a mighty legacy in three parts: music, critically-acclaimed cultural documentaries, and an archive of rich materials.

Born in Honolulu on August 4, 1927 to Alice Ululani ʻŌpūnui and Samuel Hoapili Kamae, Kamae was raised in a Hawaiian-speaking home in a mostly Chinese plantation camp near Chinatown and spent summers with his maternal grandmother in Lahaina. The musician who revolutionized ʻukulele playing by bringing it out of the rhythmic background to the solo forefront had his first experience with the instrument when he played one his older brother brought home.

The only style of music the young Eddie wasn’t interested in was the one his father asked him to play: Hawaiian, because he thought it was too simple. Instead he picked out popular tunes, Latin music, even classical works on the ʻukulele and became known for a unique way of playing both rhythm and melody at the same time. He played for tips at Charlie’s Cab Stand and then formed the ʻUkulele Rascals with Shoi Ikemi. Together they joined bandleader Ray Kinney for a coast-to-coast tour on the continental U.S. in 1949.

Eddie taught ʻukulele and played various engagements to support himself. By 1958 he was a featured soloist in Haunani Kahalewai’s Top o’ the Isle show at the Waikīkī Biltmore hotel. One night Haunani shared some sheet music with him that would change his ambivalence toward Hawaiian music. “Kuʻu Pua I Paoakalani” by Queen Liliʻuokalani touched something deep inside of him and gently set him on a lifelong path of studying, researching, reviving, and playing Hawaiian music.

In 1959, Eddie drove to Waimānalo to visit friends and found an ailing Gabby Pahinui. Gabby asked him to stay awhile and play music with him. Thanks to Gabby’s gifted and deeply Hawaiian style of playing, the impromptu request led to a month-long musical immersion and an epiphany for Eddie: “I heard the soul speaking and in almost an instant I understood what my father had tried to tell me about Hawaiian music. There in Waimānalo, just the two of us, Gabby is pouring out his heart and the whole history of Hawaiʻi is in his voice.” That day would determine the rest of Eddie’s life journey.

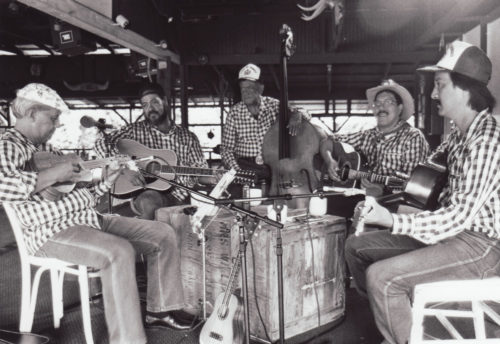

Their collaboration reinvigorated Gabby and led to the founding of one of the most famous musical groups in Hawaiʻi’s history that still, after many iterations, continues today: the Sons of Hawaiʻi. Eddie and Gabby were joined by two accomplished musicians: steel guitar player David “Feet” Rogers and bassist Joe Marshall. Together they made hugely popular albums in the 1960s and ‘70s featuring songs that drew from traditional Hawaiian chant and music but were played in a distinctive and rhythmically assertive style. Their music became part of the soundtrack to the Hawaiian cultural revival movement, a call to pay attention to the traditional values that form the bedrock of life in Hawaiʻi—including that of aloha ʻāina—values that were slipping away. In 1970 Eddie bought blue palaka shirts—a print popular during the plantation era and one that spoke to working-class pride—for the band members to wear when they played at the Hāna Hoʻolaulea Music Festival. From then on the Sons of Hawaiʻi wore palaka shirts whenever they played. Often the group introduced themselves with: “We are the Sons of Hawaiʻi and we are Hawaiian.”

During their first gig at the Sand Box in Honolulu’s Sand Island industrial area, one of their regular audience members befriended Eddie. Kurt Johnson loved the Sons’ music and invited Eddie to meet a friend of his mother’s who could help him learn more about the music he was playing. “The most knowledgeable person I know is Kawena Pukui. If you’re serious I’d like to take you to meet her,” Kurt told Eddie.

Hoʻomau Eddie, hoʻomau

Mary Kawena Pukui was Hawaiʻi’s foremost scholar of Hawaiian culture, a living treasure of cultural knowledge. A linguist, translator, genealogist, composer, kumu hula, and storyteller, she had an encyclopedic mind. She was author of over 150 songs and chants and author or co-author of fifty-two books and articles. From their first meeting Kawena would become one of the most important teachers and song collaborators in Eddie’s life. She encouraged his library and archive research but told him those alone would not take him to the heart of Hawaiian music. “It’s out there. In the valleys and small towns, in the back country. All those places where we have come from.” She told him to go there to find the songs and ʻike (knowledge) usually shared among families, something she knew was in danger of disappearing.

Kawena was generous in both mind and spirit. Eddie said, “She told me, ‘The next time you come to visit me, bring your wife for I want to meet her.’ I called one day and asked if I could see her and she said ‘hiki’ and ‘bring your wife.’ And my wife and I visited Kawena the next day. We discussed my research, translated my work. After an hour I told Kawena, ‘I’m going.’ I leaned over to kiss her and thank her. She looked at me and said, ‘If you have any pilikia with your wife Myrna you’re wrong. For your wife will be helping you in your life’s work.’”

According to Eddie, “I’d never heard a harsh word mentioned by Kawena of anyone, all the years I’d known her. Always love & respect. She would say, ‘there’s always room in your heart for forgiveness.’” He added, “my first visit to Kaʻū I would say, ‘Kawena Pukui sends her aloha.’ At that moment love was shown to me, with great affection and love for Kawena.”

“Kawena is aloha.”

“Over the years I visited Kawena at her home and shared my research. When I’m in the doorway, saying ‘mahalo’ Kawena would always tell me, ‘Hoʻomau, Eddie, hoʻomau.’”

A life-changing trip for Eddie was one he took with Kawena when she asked both Eddie and Myrna to join her in Kaʻū. They would visit the places where she grew up and learned from her grandmother. At the end of the long day, at Uncle Willie Meinecke’s home in Nāʻālehu, Kawena said to Eddie, “I would like you to meet the songwriter of Waipiʻo Valley, Sam Liʻa.” Eddie knew nothing about Sam. Kawena said, “He is the one. He is like no one else. This man writes in the old way, Eddie. No one knows how many songs, or where they all are. He writes in Hawaiian and he gives it away, with his aloha. In our time there is no one else like him.”

Play it simple, play it sweet

On Eddie’s first trip to visit Sam Liʻa he drove from Hilo to Kukuihaele and made his way to a wooden house right by the old social hall. There he found the elderly gentleman on his porch, sitting straight in his chair with a dignified air. Wearing a white shirt, tie and black suit, the man with tinted glasses, white hair and mustache said, “I’ve been expecting you.”

Samuel Liʻaokeaumoe Kalāinaina was born in 1881 in Waipiʻo Valley to Malaka and Samuel Kalāinaina, one of eleven children. In 1913 he married Sarah Kapela Kaiwipoepoe Pupulenui and had two children. In his life he had been a taro farmer, a typesetter, a wagon driver, a plasterer, a road repairer and a supervisor. But music defined him. He played the ʻukulele, guitar, banjo, piano and organ until late in life. He was the organ player for his church and taught choir with a reputation as a kind and patient teacher. He was part of, or led, several traveling serenader groups, and when asked how he managed his musicians, he said, “Let each and every one of them share their manaʻo, their intention and feeling, the way they want to play their song, and share the way they want to strum along with you. I let them do that and all I tell them is, ‘play it simple, play it sweet, don’t forget the rhythm, and don’t forget the melody line.’”

Liʻa wrote dozens and dozens of songs and gave many of them away as gifts: nāu kēia mele, this mele is for you. With a natural facility in Hawaiian as his first language and the eyes of a poet, he took in the places around him, from pristine Waipiʻo to the urban landscape of Hawaiʻi Kai and composed beautiful, thoughtful songs full of aloha for the recipient he had in mind. Sam shared many of his songs of Waipiʻo Valley with Eddie as he did in the old Hawaiian way. Eddie wrote the music for some of them and arrangements for all of them. Eddie felt privileged to sing and perform Sam’s songs.

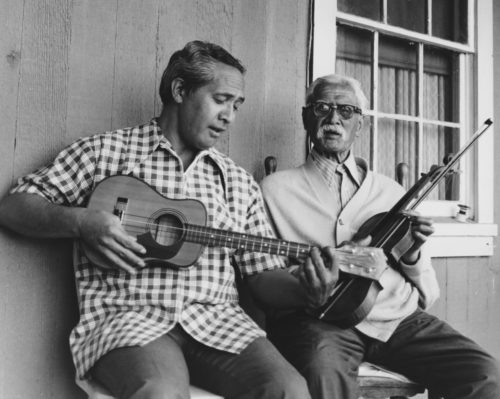

Sam and Eddie shared a close relationship of four years during which they composed together, recorded songs and chants on audiotape, roamed through Waipiʻo Valley, and shared stories. Mostly Eddie listened. They spent many hours together on Sam’s porch or in his sitting room among his song sheets, books, violin and keyboard. During one of these visits, Eddie asked him how he seemed to be expecting him. Sam explained that Kawena had written to him saying that Eddie would come to visit. If Eddie had found a spiritual father, Sam had recognized in him someone he’d been looking for and waiting to meet. Sam said, “People tend to wait for the right people to come along.”

According to Eddie, on one of the days he visited Sam, he saw a notepad in Sam’s lap. “He was working on a song. He’d written some lyrics on some pages and he tore them off, looked at me, and said, ʻThese are for you.’ I said, ʻYou give this to your family’ and he said, ʻNo, I give this to you with my aloha.’” To Eddie, Sam was a man of aloha.

Do it now, for there will be no more

Like Mary Kawena Pukui, Pilahi Paki helped guide Eddie on his journey. Hawaiian poet, philosopher, author, and teacher, she was born on Maui and was a contemporary of Kawena’s and other Hawaiians engaged in scholarly work. She was best known for her profound message about aloha at the 1970 Governor’s Conference on the Year 2000 which became a bill signed into law by then governor George Ariyoshi who said it expressed “aloha as the essence of the law in the State of Hawaiʻi.”

Eddie was also introduced to Pilahi through Kurt Johnson. Pilahi would often visit Kurt’s mother, Rachel, at her home in Hakipuʻu on Kāneʻohe Bay to discuss wide-ranging topics of Hawaiian knowledge. At their meeting, Pilahi asked Eddie, “What have you been doing?” Eddie said, “So I showed her some of my work that I’d been doing research on and she gave me her phone number and said, ‘You call me. I live in Kailua. Anytime you want to see me, talk to me, you call me.’”

Eddie and Pilahi would meet up when Eddie had questions about his research or music. He said, “I found her very stern. When she talks to you, she doesn’t smile at all. She just tells you what it’s all about. I like that. She was very generous, very caring, always reminding me, ʻYou call me if you need me.’”

Eventually the two would put Pilahi’s thoughts about aloha to music, creating the song “Aloha Chant.” Eddie remembers that Pilahi shared her vision that the spirit of aloha would one day guide a troubled world toward peace. Eddie said, “I liked that. So I did the music for “Aloha Chant.” The two would also compose one of the Sons’ most popular songs, “Kēlā Mea Whiffa” which describes a formerly foul odor at Launiupoko on Maui.

In 1979 Eddie was recognized as a Living Treasure of Hawaiʻi by the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaiʻi. At the award luncheon at the Willows restaurant, Pilahi turned to Eddie and said, “Where are you with this work you have been doing for so many years?” Eddie answered, “I am still working on it.” Pilahi then looked at Eddie and said in a stern voice he never forgot, “Do it now, for there will be no more.” At home, Eddie told Myrna what she had said.

Both recognized the urgent truth of her message. It was, in fact, the catalyst that would help launch a second career for Eddie—as a filmmaker.

A treasure trove into the worldview of kūpuna

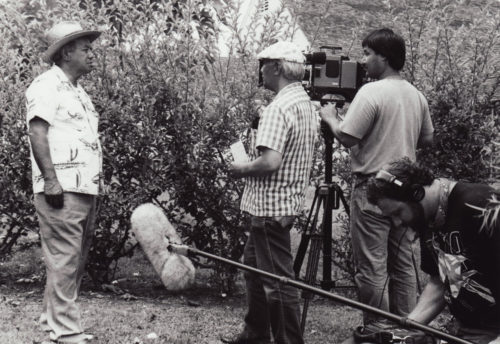

It began as a small thought, growing over time into an eighteen-year-long puzzle that Eddie wrestled with: how to best tell Sam’s story. Print? Audio recordings? New music? Once he discovered filmmaking he said, “I thought I was just going to make one film. But along the way I met so many people and learned so many stories that I had to keep on making more films.”

Collaborating with his wife of fifty years, Myrna, the pair directed and produced ten award-winning documentaries beginning with Liʻa: The Legacy of a Hawaiian Man in 1986. Their goal was Hawaiian cultural continuity: to preserve and share the firsthand accounts of kūpuna who were passing away and are mostly gone. In each, their voices, gestures, faces, songs, and memories are highlighted against music performed by the Sons of Hawaiʻi, narration by Kaʻupena Wong, and an introduction by Eddie expressing what he learned about these stories and himself.

The documentaries about Hawaiian music, culture, language, and history are a treasure trove that takes us into the worldview of our kūpuna with the hope that future generations can learn from them, remember their history, respect their cultural identity, and in turn, learn and tell their own stories. The documentaries are, through arts and cultural education, a means to recover and stabilize the loss of language and cultural identity that occurs with each passing generation.

Eddie and Myrna took the documentaries to schools across Hawaiʻi and created learning materials to accompany them. Eddie said, “I try to tell the children, ʻask your grandparents what life was like, what the sound of music was. What was the lifestyle like?’ That’s what I want them to do to keep this music alive.”

Ka ipukukui pio ʻole i ke Kauaʻula/the inextinguishable light in the Kauaʻula wind

Yet to Eddie, the body of work he and Myrna produced was not measured by accomplishments but by how much was left to be done. Eddie Kamae’s work with Hawaiian culture served as a bridge between kūpuna who shared songs, stories and traditions with him. All of his teachers and most of the kūpuna whose stories he recorded told him to “do it for the children.” So Eddie and Myrna established the Hawaiian Legacy Foundation to “continue the work” of passing on Hawaiʻi’s deep culture to future generations of learners.

This collection of songs is part of the ongoing focus of finishing Eddie and Myrna’s work so that the music can live on. In addition, efforts are ongoing to ensure that the irreplaceable materials they collected and created are archived and accessible for educational purposes.

In his search for a deeper source of understanding Hawaiian music and culture, Eddie felt like he was always guided. From locating songs at Bishop Museum’s library to finding old songwriters living in Hawaiʻi’s tiniest towns, Eddie listened to and followed the signs that were shown to him. We hope that the stories of his life in music inspire you, and when your signs appear, that you, too, will follow them.